How Reducing Waste Is a Climate Changer?

Waste mismanagement has several environmental and climate negative impacts. What if combining upstream measures and actions at the city level can drastically decrease cities’ emissions, reduce flooding risks, strengthen environmental resilience, and beyond environmental and climate mitigation, provide substantial public health and economic benefits?

After publishing the report “Zero Waste for Zero Emissions: How Reducing Waste is a Climate Changer” By the Non-profit Global Alliance of Incineration Alternatives (GAIA), Captain Forest interviewed Doun Moon, a policy researcher in Korea working for this NGO. She shared with us the main findings of the report and explained how reducing waste is a climate changer. (1)

Q: What are the different categories of waste?

The following categories (2) are typically used by most countries worldwide. Usually, we split waste into two categories:

- Hazardous waste: radioactive and industrial waste,

- Non-hazardous waste: municipal waste and non-hazardous industrial waste.

GAIA study (1) focuses only on municipal waste – consisting of daily items discarded by people – which includes:

- Organic waste,

- Packaging waste,

- Other materials, such as glass, plastic, metal, etc.

Q: Can you give an overview of the global waste crisis?

There is extensive literature available on the global waste crisis. Let me share a few essential facts and figures:

- By 2050, experts expect an increase in waste generation by 70 percent, from 2.01 billion tonnes of waste in 2016 to 3.40 billion tonnes annually.

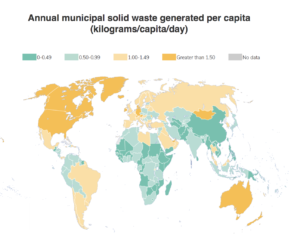

- According to a study by The World Bank (3), waste generation is proportional to the national income level and increases with growing urbanization. Therefore, high-income countries generate more waste than low-income countries.

This study by the World Bank shows that together Africa and the Middle East generate 15% of worldwide waste, representing 21% of the global population.

By comparison, Together Europe and North America generate 34% of worldwide waste, representing 16% of the global population. (3) (4)

- Globally, waste end of life is managed or mismanaged in this way (3):

- 69% of waste is disposed of in landfills (36%) or openly dumped (33%),

- 11% is treated through incineration,

- And 19% undergo materials recovery through recycling and composting.

- Regarding the plastic end-of-life data between 1950 and 2015 (5):

-

- 79% of plastic waste is landfilled or dumped,

- 12% incinerated,

- And only 9% were recycled (including downcycled, i.e., recycled into an item of a different/lower value such as plastic-to-road).

These figures show how difficult it is for municipalities to manage their waste and especially when it comes to plastic.

Much waste is simply disposed of in landfills or treated through incineration. As a result, it worsens the environmental and climate crisis.

If by 2050, the amount of waste generated doubles compared to 2016 levels, then what would be the impact?

Q: Can you explain the social, environmental, and climate impacts of waste mismanagement?

Environmental and health impacts of incineration (6)

Waste and plastic waste management technologies (including incineration, co-incineration, gasification, and pyrolysis) result in the release of toxic metals, such as:

- Lead and mercury,

- Organic substances like dioxins and furans,

- Acid gasses,

- And other toxic substances.

Burning leads to direct and indirect exposure to these toxic substances harming both the environment and animals and human health:

- Workers and residents in nearby communities inhale polluted air, are in contact with contaminated soil or water, and ingest foods that were grown in an environment infected with these substances,

- Toxins from emissions, fly ash, and slag in a burn pile can travel long distances and deposit in soil and water, eventually entering human bodies after accumulating in plants and animal tissues.

Climate impacts of waste mismanagement:

Climate impact on the whole material economy (7)

The material economy is the linear production system that runs on five steps: extraction, production, distribution, consumption, and disposal.

In such an economy, the production and consumption of all used materials contribute to increasing greenhouse gas emissions.

As seventy percent of global greenhouse emissions come from the material economy, from extraction to disposal, it considerably impacts climate.

Climate impact of plastic waste (8)

Burning plastic leads to extremely high greenhouse gas emissions. Waste incineration — whether in the form of “energy recovery”, co-firing in cement kilns, waste-derived fuels, or even open burning— is the primary source of greenhouse gas emissions from plastic waste management, even after considering energy generation potential.

Burning plastic emits 2.7 tonnes of CO2 e for every tonne of plastic burned; even when energy recovered in a waste-to-energy incinerator is accounted for, burning one tonne of plastic in an incinerator still results in 1.43 tonnes of CO2 e.

Beyond the climate impact of plastic when burned at its end of life, it’s important to mention that plastic results in massive emissions at each stage of its lifecycle – from the extraction of fossil fuels, refining, plastic manufacturing, transport, and disposal.

Ninety-nine percent of plastic manufactured today comes from fossil fuels.

Often emissions are overlooked from oil and gas drilling, transport, and refining. There are direct and indirect emissions from electricity and heat, process CO2 emissions, and emissions of non-CO2 greenhouse gases.

The global carbon footprint of plastic throughout its entire lifecycle was estimated at 1.7 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent (CO2 e) in 2015, which would grow to 6.5 billion tonnes of CO2 e (equivalent to annual emissions from nearly 1,640 coal-fired power plants) by 2050 if the production, disposal, and incineration of plastic continue on their present growth trajectories.

Consequently, by 2050, emissions from plastic alone will take up over a third of the remaining carbon budget for a 1.5 °C target. (9)

Climate impact of organic waste in landfills:

Methane is a powerful GHG, trapping 82.5 times as much heat as CO2 over a 20-year timespan. It is responsible for approximately 0.5°C of warming in today’s world.

Globally, the waste sector is responsible for approximately 20% of anthropogenic methane emissions, making it the third largest and most rapidly growing source sector. (9)

Landfill methane emissions result from the decomposition of organic waste – primarily food scraps – under anaerobic (oxygen-deprived) conditions. In some cities, landfills are the dominant source of methane emissions.

Q: Who are the actors that we need to involve in a systemic change? And what actions can they take?

The waste crisis is a systemic issue. Our NGO GAIA advocates for a system change rather than individual behavior change. GAIA raises concerns about excessive mass production and consumption of materials, including plastic and organics.

We think municipalities and producers are the stakeholders who need to take action.

How cities can reduce waste?

There is no standard answer to this question because each city has different infrastructures and systems.

For example, San Francisco has progressive policies and a good waste management system, as less than 1% of its waste is incinerated. San Francisco relies a lot on composting to process organic waste, which avoids landfill methane emissions.

For example, San Francisco has progressive policies and a good waste management system, as less than 1% of its waste is incinerated. San Francisco relies a lot on composting to process organic waste, which avoids landfill methane emissions.

In developed countries, cities generally follow a zero-waste master plan that helps them assess their collection system.

In developing countries, cities usually have less efficient waste management systems, and in rural areas, local populations need to manage their waste.

Overall, cities can do the following:

- Incorporate zero waste goals and policies into climate mitigation and adaptation plans,

- Ban single-use plastics and packaging,

- Separate the collection and treatment of organic waste,

- Invest in recycling and composting systems.

How companies can reduce waste?

The most important thing is that companies take responsibility for their products and operations and stop greenwashing.

For example, offsetting pollution with plastic or carbon credits makes no sense.

Instead, they need to take real and concrete actions like changing their packaging and distribution system and transforming their operations to embrace circular economy principles.

Q: Why is reducing waste at the city level a climate changer?

There are two significant sources of GHG:

- Plastic which emits GHG at each phase of its lifecycle and when burned at its end of life,

- Organic waste in landfills emits methane.

We can significantly reduce GHG emissions by tackling those two issues – plastic and organic waste management.

GAIA case study learning

Our study looked at eight cities worldwide that reduced their waste amount, and we measured their climate impacts.

- Bandung, Indonesia

- Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

- Detroit, USA

- Durban, South Africa

- Lviv, Ukraine

- São Paulo, Brazil

- Seoul, Korea

- Temuco, Chile

As a result, we learned through these eight case studies that upstream reductions, particularly in food and plastic, can trigger significant GHG emissions reductions throughout the supply chain and in the waste sector.

We also learned downstream that source-separated collection and treatment of organic waste are essential to reduce emissions – 43% to 83%- even with incomplete implementation.

Moreover, burning waste whether with energy recovery or not, results in massive GHG.

In Dar Es Salaam, the only city in this study with widescale open burning, we learned that ending this practice would reduce GHG emissions almost half as much as ending landfill methane emissions (in addition to significant public health benefits).

Finally, recycling creates the possibility of a net-negative waste sector. Increased recycling reduced emissions between 3% and 35%. However, current recycling rates are lower than technically possible because of a lack of financial incentives.

Q: Why is energy recovery not an effective climate mitigation strategy?

When we speak about energy recovery, we refer to two practices:

- Generation of energy from waste: like for incineration, facilities need combustible material to keep the fire burning, and usually, this material comes from fossil fuels as combustion needs high temperatures. Consequently, there is a high amount of GHG emitted, and we can reasonably claim this is not a climate solution but a climate disaster. Moreover, beyond GHG emissions, toxic substances are released into the atmosphere (such as ash) and threaten local populations’ health.

- Recovering gas in landfills: this practice consists of capturing methane emitted in landfills. When this technique works, it’s indeed good but not always reliable because a lot of methane is released into the air and it is difficult to capture it all.

Energy recovery is not an effective climate mitigation strategy, and we must first reduce the amount of waste. (10)

Q: Beyond climate, what are the environmental and social benefits of waste reduction for cities?

Waste reduction has several benefits at the environmental level, such as saving natural resources, protecting ecosystem health, and reducing ecological stressors associated with waste disposal facilities.

There are also benefits at the societal level: cities improve their water and food security and decrease climate and disease transmission risks.

Water and Food Security

For example, both compost and biodigester (an output from anaerobic digestion) have a beneficial impact on waste management and agriculture: by providing nutrients for the soil, they increase soil fertility and its capacity to hold water, thus supporting food and water ecosystems.

Climate risks

The combination of the plastic ban and universal collection systems is critical to flood prevention in a city.

Disease risks

By improving waste collection systems, cities avoid disease risks. Uncollected waste, especially plastic, creates a habitat for disease vectors, while food waste provides a food supply for vermin.

Waste reduction reduces the risks of certain illnesses, such as cancer, because of the spread of toxic ash and chemicals from incinerators and landfills by rendering them redundant.

There are also economic benefits for proper waste management as it creates better employment opportunities than traditional waste management jobs, reduces poverty by including informal waste pickers, and opens the door to innovative businesses.

Finally, zero waste systems are more collaborative and bring together a wide range of stakeholders, improving democracy in society.

Q: What are the top five best cities in the world in terms of waste management?

There are great examples of cities that successfully manage their waste. I will cite more than five cities:

- In the USA,

- San Francisco: they have a minimal incineration policy and achieved an 80% waste diversion rate,

- In Asia,

- San Fernando in the Philippines impressively improved their waste diversion in a short time,

- and Trivandrum in Kerala, India, which has a good organics management system.

- In Europe,

- Capannori in Italy, which is considered a zero-waste pioneer in Europe.

- In South America:

- Buenos Aires for their waste pickers inclusion program,

- Sao Paulo has a tremendous organic waste program.

- In Africa:

- Kigali in Rwanda has progressive plastic bans policies at the national level,

- Nairobi and Accra as they have multiple civil society organizations focusing on diversion from landfill and active waste management policy conversation.

Q: To conclude, what are your recommendations for cities and companies?

We recommend source reduction as a first step. That’s why companies need to take action to reduce the production of goods and packaging, which leads to waste generation.

Then at the city level, municipalities need to:

- Recognize the interlinkages between the environmental and climate crisis and waste management,

- Assess the city’s waste system to increase rate collection,

- Prioritize food waste prevention and single-use plastic bans

- Institute separate collection and treatment of organic waste,

- Refuse incineration,

- And recycle remaining waste.

Sources:

- (1) GAIA report zero-waste to zero-emissions

- (2) https://sisu.ut.ee/waste/book/11-definition-and-classification-waste

- (3) https://datatopics.worldbank.org/what-a-waste/

- (4) Population Data – World Bank

- (5) https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.1700782

- (6) https://www.ciel.org/plasticandhealth/

- (7) https://www.circle-economy.com/

- (8) https://www.ciel.org/plasticandclimate/

- (9) https://www.no-burn.org/resources/methane-report/

- (10) https://www.newswire.com/news/the-global-methane-hub-sron-and-ghgsat-launch-world-first-project-to-21867524